Havoc

Spinal Tumor, Nephroblastoma

Home » Case Studies » Havoc

Havoc, an 18-month-old intact male Siberian Husky, presented to Southeast Veterinary Neurology for progressive rear limb weakness.

Havoc first presented to his primary veterinarian for evaluation of lameness that progressed to weakness and scuffing his rear limbs. Spinal radiographs (X-rays) were performed by his veterinarian, which appeared normal.

When Havoc’s condition continued to decline, he was immediately referred to Southeast Veterinary Neurology (SEVN) for further evaluation. He was evaluated on an emergency basis that same Saturday evening.

During his initial neurologic evaluation, Havoc was bright, alert, responsive, and behaving appropriately. All cranial nerve reflexes and responses were intact. However, there was minimal motor function in the rear limbs. The front limbs appeared normal. Havoc was still able to wag his tail, indicating non-ambulatory paraparesis. Non-ambulatory paraparetic dogs are still able to move their legs and wag their tails, but are not strong enough to support their own weight and walk.

His examination suggested a neurological problem affecting his T3-L3 (mid-back) spinal cord. Possible causes included a slipped disc (most common, but typically painful), a fibrocartilagenous embolism (non-painful, but typically not progressive), meningomyelitis (not a typical breed and often painful), infection (again, often painful), a congenital malformation (he’s young, but not so young as to consider this highly), or cancer (although he is considered quite young for spinal neoplasia).

A CBC and chemistry panel were normal for his age and thoracic radiographs did not show any abnormalities.

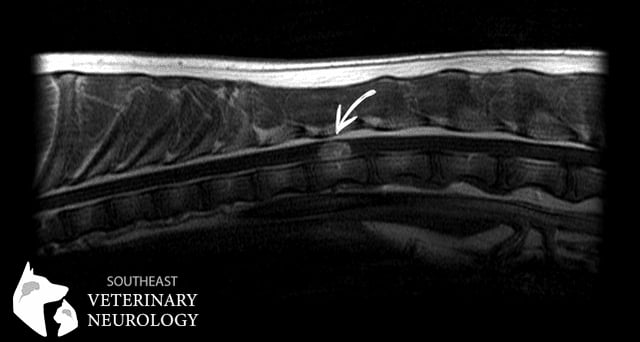

Havoc was placed under anesthesia and an MRI of his thoracolumbar spine was performed (pictured below).

The MRI images revealed a focal, well-defined, left-sided, contrast enhancing, intradural/extramedullary spinal cord mass at the level of the T12 vertebral segment. When a tumor is intradural and extramedullary, it means that it is located in the dura (covering of the spinal cord), but that it is not in the tissue of the spinal cord. There was associated swelling of the spinal cord in the region surrounding the mass.

This was considered highly unusual. There are only a handful of possible causes for intradural/extramedullary spinal masses. Meningiomas are the most common tumor in this location. Peripheral nerve sheath tumors, granulomas, and hemorrhage can be found here as well. However, the primary consideration was for a type of tumor called a nephroblastoma, as these are classically intradural/extramedullary, and found in the thoracolumbar region of young large-breed dogs.

The owner elected surgical excision (removal) of the mass and allowed for subsequent histopathologic evaluation to obtain a definitive diagnosis. A left-sided T11-T13 hemilaminectomy with subsequent removal of the mass was performed by Dr. De Pompa.

At surgery, the mass grossly appeared tan to dark red with a thin purple peripheral rim. The dorsal aspect of the mass appeared encapsulated and was teased away from the adjacent spinal cord relatively easily. The ventral aspect was not easily isolated from the spinal cord. Careful, blunt dissection was required to tease the mass away from interdigitating spinal cord fibers.

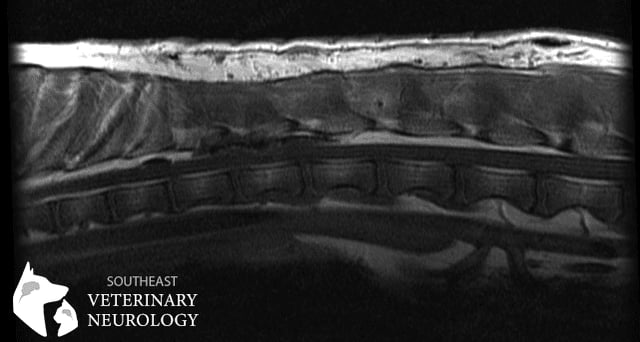

A post-operative MRI was performed, which suggested successful macroscopic removal (pictured below).

Havoc was hospitalized for several days after surgery for pain management, nursing care, and physical therapy. He regained the ability to walk quite quickly after surgery and is doing well at the time of this article. We are amazed at his resiliency. Full recovery may take time, but his progress was impressive taking into account how extensive the mass was.

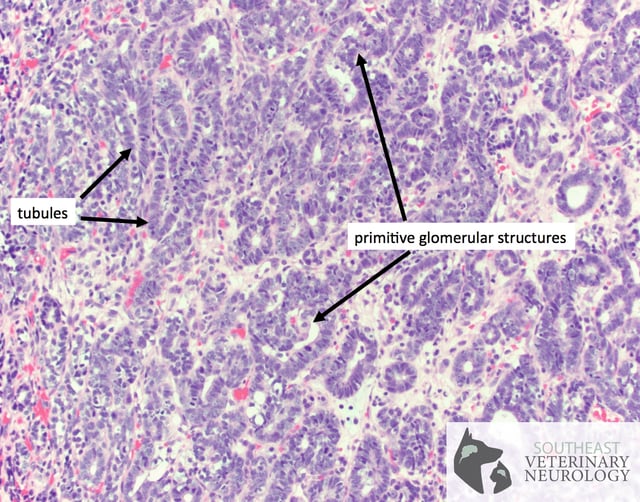

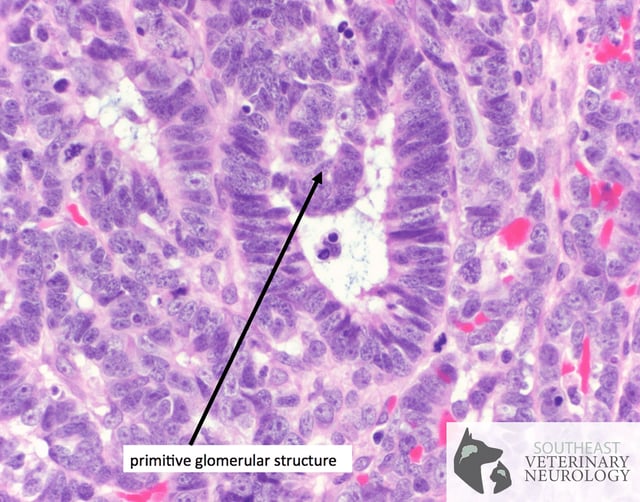

Both gross and microscopic findings were consistent with a primary central nervous system nephroblastoma.

Nephroblastoma, also known as Wilms’ tumor in human medicine, is a primordial cancer thought to originate from ectopic metanephric blastemal cells. A spinal nephroblastoma is a specific condition where these cells are entrapped within the spinal canal during embryogenesis, and subsequently adopt neoplastic behavior some time later in life. Spinal nephroblastomas in animals are quite rare. Nephroblastoma treatment options are limited, with surgical debulking (removal) as the primary treatment option in veterinary medicine. Subsequent radiation therapy following surgery is thought to be of added benefit.

Havoc’s case was unique in many ways. Given his young age and rapid onset, cancer would typically not be high on the list of possible causes. Cancer is generally thought to be associated with chronic progressive changes that slowly develop over time. Additionally, cancer is more commonly diagnosed in older patients.

Havoc reminds us to keep an open mind about the possible causes and highlights how well pets can do even when severely affected with spinal cancer.