Milo

Skull Fracture & AO Luxation

Home » Case Studies » Milo

History

Milo, a 1.5-year-old intact male Pomeranian, presented to Southeast Veterinary Neurology for inability to walk after being hit by a car.

Immediately following the car accident, Milo had been taken to an emergency animal hospital for stabilization. No fractures were reported, but when Milo became more mentally alert, he was unable to walk. At that point, he was referred to Southeast Veterinary Neurology for further evaluation and treatment.

Examination

Upon examination, Milo was quiet. He displayed non-ambulatory (unable to walk) tetraparesis (weakness in all four limbs), with mild motor function in all four limbs when supported. Postural reactions (responses that help maintain a normal, upright position) were absent in all four limbs, and spontaneous horizontal nystagmus (abnormal eye movement) was observed. Spinal reflexes appeared normal, and Milo did not seem to be feeling any pain.

Based on the examination findings, Milo’s neuroanatomical localization was in the caudal fossa (the back of the skull containing the brainstem and cerebellum) and affecting his vestibular system (responsible for balance). MRI and CT scans were ordered to further evaluate this region.

Labs & Imaging

Thoracic (chest) radiographs from the emergency animal hospital were normal. Blood work at Southeast Veterinary Neurology indicated mild anemia and elevated ALT (liver enzyme). However, no anesthetic contraindications were noted.

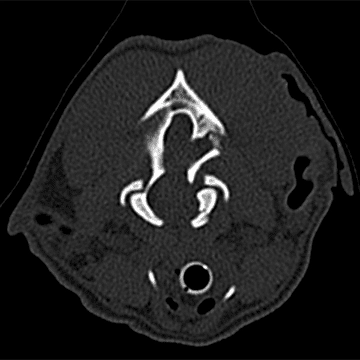

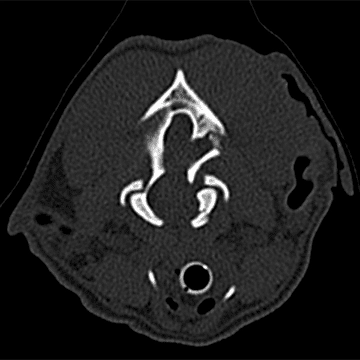

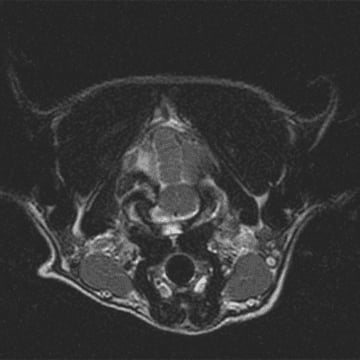

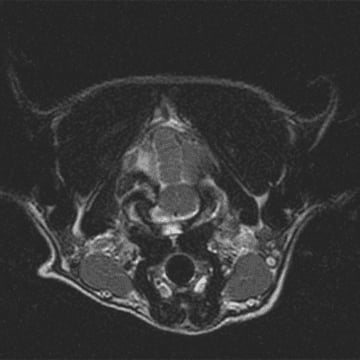

High-field MRI of Milo’s brain was performed in multiple planes and sequences including T2W, T1W, and FLAIR, and IV contrast was administered. A skeletal fragment causing compression of the left cerebellar hemisphere and brainstem was discovered, with T2 hyperintensity of the adjacent cerebellar tissue and T1 isointense material filling the left tympanic bulla.

CT showed closed complete comminuted (more than two pieces) variably displaced traumatic fractures of the left petrous temporal bone, left occipital bone, and occipital condyle with secondary subluxation (partial dislocation), extra axial compression of the medulla oblongata and cerebellum, left tympanic cavity effusion (likely hemorrhagic), and superficial subcutaneous edema and/or hemorrhage.

In summary, MRI and CT revealed a fracture of the occipital bone at the back of the skull, which was compressing the cerebellum and brainstem, and also a fracture of the occipital condyle, where the skull connects to the first vertebra (AO luxation).

Treatment

In order to give Milo the best chance of recovery, he was taken into surgery, and the largest, most compressive of the fragments was removed.

Milo initially had periods of respiratory insufficiency and fluctuating blood pressure upon recovery, which was stabilized. Over the next several days, Milo gradually regained the ability to walk before being discharged from the hospital.

Milo was sent home with strict instructions to stay confined in a well-padded space, except when carried outside to relieve himself on a leash and harness. The full extent of Milo’s recovery will take a few months. Healing of bone generally takes 8 weeks, but because this area is attached to a joint, some movement will be unavoidable. Therefore, he was prescribed a full 12 weeks of rest with a follow-up CT scan to check his healing after that.

During this time, it is critical to avoid any impact to the back of the head where the fractured condyle is located. If Milo were to fall, jump, or even move excessively during his recovery he could dislocate his head, resulting in death.

In the meantime, Milo’s owners report that he is doing very well at home.

Takeaway

Atlanto-occipital (AO) luxation, sometimes referred to as internal decapitation, is not often mentioned in veterinary literature because of its high rate of mortality. In the extraordinary case of survival, like Milo, timely diagnosis and treatment, as well as proper supportive care, are critical for positive patient outcome.

Milo’s case teaches us the importance of seeing a specialist. What the emergency hospital could not see, a veterinary neurologist with specialized experience and equipment was able to recognize, confirm, and treat promptly. Had Milo not been immediately referred to the experts at Southeast Veterinary Neurology, he would not be alive today.