Dolce

Encephalitis, Vestibular Disease

Home » Case Studies » Dolce

Dolce, a 3-year-old FS Chihuahua, presented to Southeast Veterinary Neurology for evaluation. Approximately 9 days prior to presentation, she fell down the stairs. A few days after the event, the owners noticed that Dolce seemed weak in her rear limbs and had an arched back.

She was evaluated by her primary care veterinarian, who performed radiographs and prescribed pain medications. The following night, Dolce vomited multiple times, and started rolling to her side.

Dolce was evaluated by her local after hours/emergency service, who hospitalized and stabilized her. She was then referred to SEVN for further evaluation.

The following is her examination at presentation.

Note that on the video, she is rolling toward the right. She is alert and responsive. It was nearly impossible to check her proprioception (paw placement) due to how much she was rolling. On cranial nerve examination, she had an absent menace response in both eyes, with a normal palpebral reflex and normal PLR (not shown). There was decreased nasal sensation bilaterally. There was positional horizontal nystagmus with the fast phase toward the left. The right eye had ventral strabismus while the left eye had dorsal strabismus. Her gag reflex was normal, with normal facial muscle symmetry and normal tongue symmetry.

Based on this information, we localized her problem to the vestibular system. The classic signs of a problem affecting the vestibular system include head tilt, leaning/falling/rolling to one side, abnormal eye movements (nystagmus) and abnormal eye position (strabismus).

The next step is to determine what part of the vestibular system is affected. The vestibular system can be thought of as two parts: the peripheral vestibular system (the receptors in the inner ear and the vestibular portion of cranial nerve VIII) and the central vestibular system (the vestibular nuclei within the brainstem and the cerebellum).

A complete neurological examination helps us determine this. Since both peripheral and central vestibular disease can have head tilt, nystagmus, leaning/falling/rolling to one side and strabismus, determining whether the problem is affecting the central or peripheral vestibular system is based on detecting additional signs that cannot be explained with a problem affecting the inner ear.

There are several other structures that are located within the brainstem, near the vestibular nuclei. These include parts of the brain responsible for the level of consciousness, several other cranial nerve nuclei, pathways for moving the limbs or for knowledge of where the limbs are in space, and the cerebellum. By looking for problems affecting one of these systems, we can better determine if the problem is affecting the central or peripheral vestibular system.

First, the level of consciousness should be normal in a pet with peripheral vestibular disease. Many times, patients are anxious, so this should be taken into account. Decreased levels of consciousness suggest a problem affecting the central vestibular system.

Second, evaluation of cranial nerves. We look at the character of the nystagmus. Both peripheral and central vestibular disease can cause horizontal and/or rotary nystagmus. However, the presence of vertical nystagmus indicates a central vestibular localization. Additionally, the nuclei of cranial nerves V and XII are in this region of the brainstem. Recognizing decreased nasal/facial sensation suggests a problem affecting CN V or it’s nucleus. Recognizing tongue atrophy suggests a problem affecting CN XII or it’s nucleus. Dolce showed evidence of decreased nasal and facial sensation.

Third, evaluation of postural reactions. Sometimes this can be challenging if a pet is severely off balance and rolling. Postural reaction deficits would not be expected in a pet with peripheral vestibular disease. However, the information for knowledge of where the paws are placed travels through the part of the brain where the vestibular nuclei are located, so causes of central vestibular disease can cause postural reaction deficits, typically on the same side as where the problem is.

Next, evaluation for signs of cerebellar disease. Signs of cerebellar disease include intention tremor, hypermetria, and truncal sway. Sometimes cerebellar disease can cause an absent menace response.

Recognizing any of these signs: vertical nystagmus, cranial nerve deficits other than cranial nerve VII (facial nerve), decreased level of consciousness, postural reaction deficits (especially when unilateral) or cerebellar signs all suggest a problem affecting the central vestibular system.

Based on this, we localized Dolce’s problem to the central vestibular system. Possible causes for central vestibular disease include encephalitis or inflammation of the brain, a stroke, a tumor, metronidazole toxicity, intracranial extension of otitis media/interna, or less likely infections.

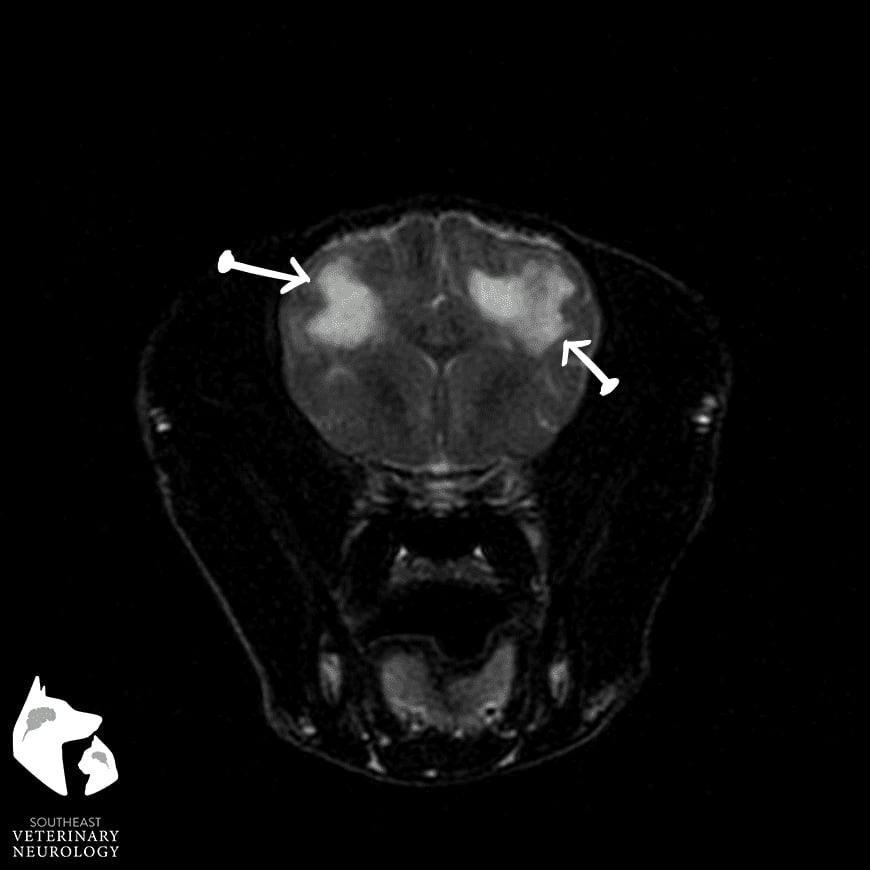

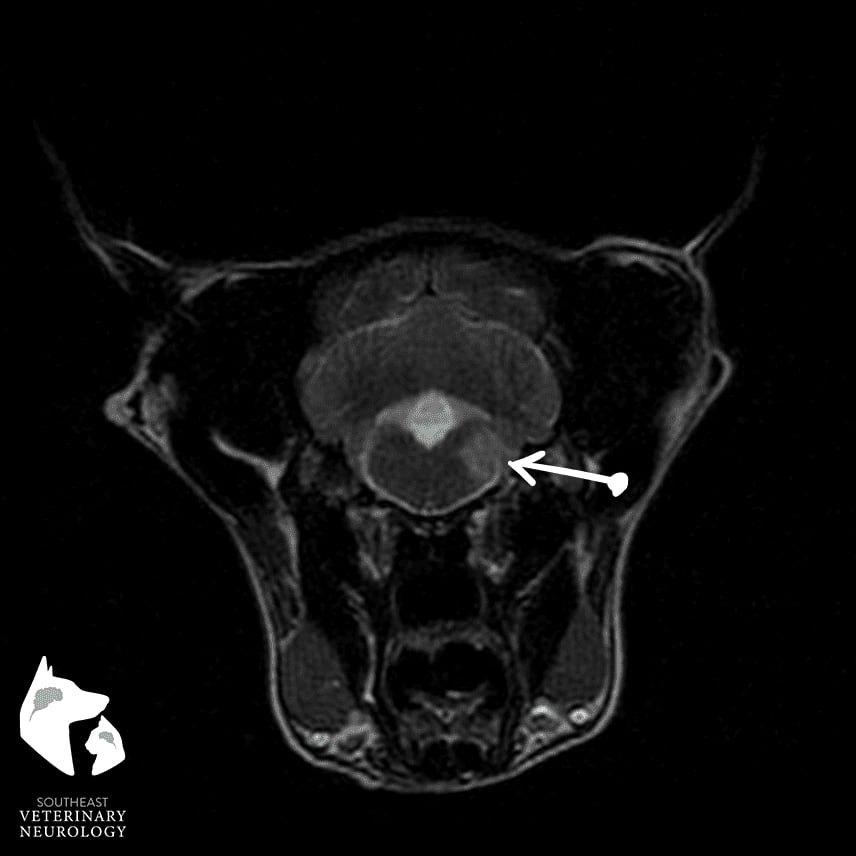

An MRI was recommended as the best test to evaluate Dolce’s vestibular system. CT scans are typically not sensitive enough to evaluate the entire vestibular system and are considered below the standard of care. Two images from Dolce’s MRI are provided below.

The first image is a T2-weighted MRI at the level of the parietal lobe of the cerebral cortex (more rostral portion of the brain). Note that there are two hyperintense (or bright) regions, in both the left and right cerebral hemispheres. They are predominately within the white matter tracts. The second image (image on the right, whatever you decide looks best) is further caudal in the brain, at the level of the vestibular nuclei. Note the well-demarcated, T2 hyperintensity with the right medulla oblongata. These areas were slightly hypointense (dark) on T1 weighted images and exhibited contrast enhancement at the periphery.

This was suggestive of necrotizing encephalitis. A CSF analysis was supportive of this as well.

Encephalitis in dogs is typically autoimmune. Treatment is based on immunosuppression. At Southeast Veterinary Neurology, we use prednisone in combination with cytarabine for the majority of patients.

Prognosis is considered guarded, in that approximately 40% of patients will respond well to medications, 40% will respond but will have relapses and the medications will need to be adjusted and 20% do not respond at all. This is far better than even 15-20 years ago. The improvement in prognosis is likely due to several things. First, with the availability of MRI, we are able to diagnose these more accurately than previously when CT scans or no advanced imaging was performed. The second factor is that veterinarians are recognizing signs sooner and, if available, are involving a specialist in neurology. The third factor is the use of additional immunosuppressants, such as cytarabine. These factors highlight the importance of bringing the pet to a veterinarian as soon as possible, recognition of vestibular disease by the veterinarian, referral for an evaluation by a neurologist and MRI, and early, aggressive, appropriate treatment.